Stephanie Hargrave

https://stephaniehargraveart.wordpress.com

[email protected]

Phone 206.227.5332

semantic drift

Semantic Drift (Installation Version 1 – M.David & Co., Brooklyn, NY)

Semantic Drift (Installation Version 1 – M.David & Co., Brooklyn, NY)

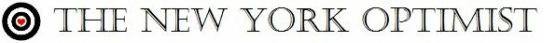

The below are the handmade elements that were later used in my residency project – all are made with cotton string, yarn, embroidery threat, steel wire and some have dried pods.

statement

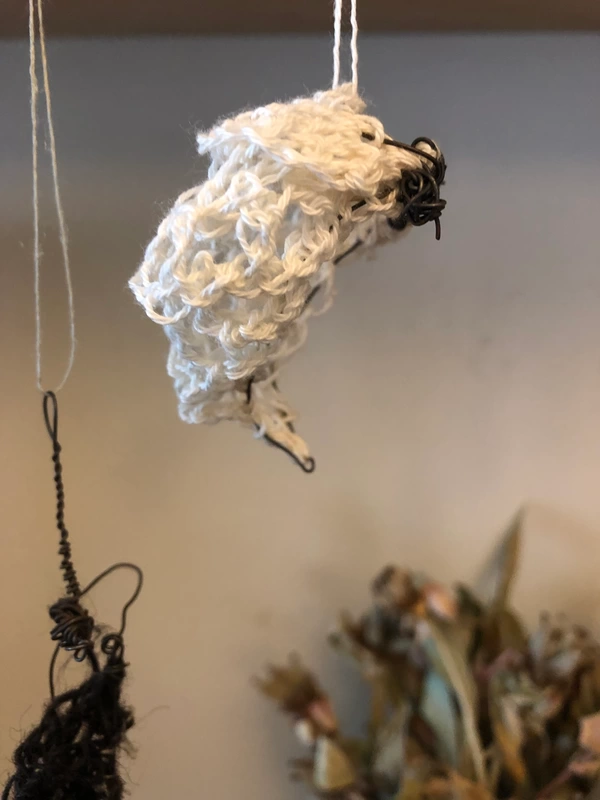

Hargrave’s work has always referenced biology. Prior work centered on botany, organisms, and cellular structures, but most recently she has concentrated on insects, fungi, bones and horns, organs, synapses, and sea creatures. Abstracting the body, on both a macro and micro level, is a custom that has grown over the years.

She submerged herself in the study of deep-sea creatures and bioluminescence that resulted in a series of black, dark Prussian blue and white encaustic paintings call Hybrid, many resembling x-rays and angiograms. At M. David & Co in Brooklyn she created an installation that combined etymology and entomology; the concept was arthropods and the words once used to refer to them that are no longer in use. Titled Semantic Drift it included photographs of crocheted insect-like forms printed on Kozo paper, infused with beeswax, and attached a half inch out from the wall with specimen pins. The originals, crocheted cotton string dyed black, were bundled together, titled Biomass, and hung from the ceiling near her metal wall sculpture whose shadow cast an uncanny resemblance to a dragonfly wing.

Her porcelain sculpture Magical Thinking is a torso sized grouping of hand pinched bell-like forms finished in black encaustic that pays homage to the medicinal qualities of mushrooms. Hung freely, it sways slowly with the air movement in the room and floats visually, in blatant disregard to its weight.

Whatever her focus, the underlying premise is a constant; biological functioning, and how we understand ourselves and the world we live in from that perspective. Abstracting those ideas and generating organic-looking objects allows for a wide array of entry points into the work and encourages various interpretations. Natural forms made from natural materials is key, but not necessary. She works mainly with clay, wood, steel, beeswax, and paper but whatever assists with the visual message is what gets used. Recently Yupo, a smooth synthetic paper that allows for wonderful gradations as the ink evaporates off the non-porous surface, has been incorporated.

The most satisfying aspect of her practice is the making itself but seeing how the work hits an audience is vital: that is where connections are made and vault naturally into new ideas. This process mimics biological functioning and completes the circle.

Hargrave’s work has always referenced biology. Prior work centered on botany, organisms, and cellular structures, but most recently she has concentrated on insects, fungi, bones and horns, organs, synapses, and sea creatures. Abstracting the body, on both a macro and micro level, is a custom that has grown over the years.

She submerged herself in the study of deep-sea creatures and bioluminescence that resulted in a series of black, dark Prussian blue and white encaustic paintings call Hybrid, many resembling x-rays and angiograms. At M. David & Co in Brooklyn she created an installation that combined etymology and entomology; the concept was arthropods and the words once used to refer to them that are no longer in use. Titled Semantic Drift it included photographs of crocheted insect-like forms printed on Kozo paper, infused with beeswax, and attached a half inch out from the wall with specimen pins. The originals, crocheted cotton string dyed black, were bundled together, titled Biomass, and hung from the ceiling near her metal wall sculpture whose shadow cast an uncanny resemblance to a dragonfly wing.

Her porcelain sculpture Magical Thinking is a torso sized grouping of hand pinched bell-like forms finished in black encaustic that pays homage to the medicinal qualities of mushrooms. Hung freely, it sways slowly with the air movement in the room and floats visually, in blatant disregard to its weight.

Whatever her focus, the underlying premise is a constant; biological functioning, and how we understand ourselves and the world we live in from that perspective. Abstracting those ideas and generating organic-looking objects allows for a wide array of entry points into the work and encourages various interpretations. Natural forms made from natural materials is key, but not necessary. She works mainly with clay, wood, steel, beeswax, and paper but whatever assists with the visual message is what gets used. Recently Yupo, a smooth synthetic paper that allows for wonderful gradations as the ink evaporates off the non-porous surface, has been incorporated.

The most satisfying aspect of her practice is the making itself but seeing how the work hits an audience is vital: that is where connections are made and vault naturally into new ideas. This process mimics biological functioning and completes the circle.

Paintings

orbita series

hybrid series

May 2019

When making my 2017 show Biota, I was inspired by a little planthopper that had evolved a small bio-gear in its hind legs. I thought of it as a perfect mechanical/insect hybrid. An early idea for the show was to paint abstract versions of hybrids, but it didn’t really come about–I went into insects, then political art for a bit, then back to insects as themes. But I really liked the idea of blending animals with insects, flowers with bugs, goats with blooms or dragonflies or whatever came about. There is a lovely egalitarianism I associate with creating hybrids.

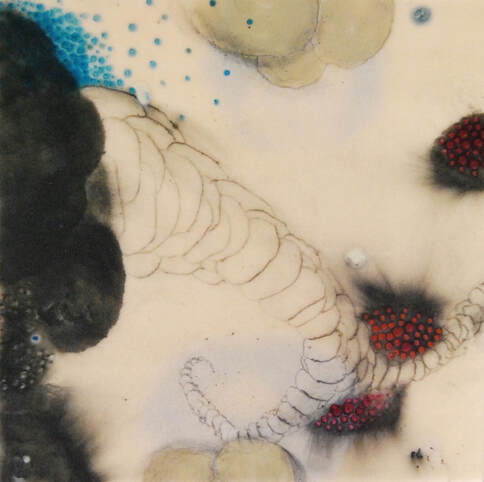

As I began working with Michael David before his NY Art Fair Residency in early 2019, I was experimenting with black and white. By the time I came home I had a renewed energy for pushing them forward. With his guidance and suggestions, I started making pieces that got closer and closer to what I was trying to express. Visually they are completely different from my other work. I paid less attention to the design and more attention to my intuition. They felt more painterly than planned out. Because they are encaustic, whatever brushiness they had melted into soft swirls and smooth washes of light over dark.

One afternoon during a facetime meeting, Michael suggesting adding Prussian blue over the black to make it a bit more palatable, and it was like magic. These somewhat spooky images became more medical feeling, and the light transparent washes of the Prussian added an intensity. They also reminded me of the angiogram I’d seen of my dad’s heart at the hospital after surgery (yes I’m planning on painting his angiogram images).

I had been studying a book of x-rays from the 1980’s I found in a junk store, and was hoping to make work that resembled parts of plants, animals and humans as well as x-rays. They became an odd blend of cattle and deep-sea fish. Some reminded me of urchins or owls—some resembled gills, bones, snakes, horns, ghosts, jelly fish, sea cucumbers and the occasional goat.

When making my 2017 show Biota, I was inspired by a little planthopper that had evolved a small bio-gear in its hind legs. I thought of it as a perfect mechanical/insect hybrid. An early idea for the show was to paint abstract versions of hybrids, but it didn’t really come about–I went into insects, then political art for a bit, then back to insects as themes. But I really liked the idea of blending animals with insects, flowers with bugs, goats with blooms or dragonflies or whatever came about. There is a lovely egalitarianism I associate with creating hybrids.

As I began working with Michael David before his NY Art Fair Residency in early 2019, I was experimenting with black and white. By the time I came home I had a renewed energy for pushing them forward. With his guidance and suggestions, I started making pieces that got closer and closer to what I was trying to express. Visually they are completely different from my other work. I paid less attention to the design and more attention to my intuition. They felt more painterly than planned out. Because they are encaustic, whatever brushiness they had melted into soft swirls and smooth washes of light over dark.

One afternoon during a facetime meeting, Michael suggesting adding Prussian blue over the black to make it a bit more palatable, and it was like magic. These somewhat spooky images became more medical feeling, and the light transparent washes of the Prussian added an intensity. They also reminded me of the angiogram I’d seen of my dad’s heart at the hospital after surgery (yes I’m planning on painting his angiogram images).

I had been studying a book of x-rays from the 1980’s I found in a junk store, and was hoping to make work that resembled parts of plants, animals and humans as well as x-rays. They became an odd blend of cattle and deep-sea fish. Some reminded me of urchins or owls—some resembled gills, bones, snakes, horns, ghosts, jelly fish, sea cucumbers and the occasional goat.

Biota

Amass

Issus Coleoptratus 2

Shift Gallery, January 2017

BIOTA

Biota is a succinct word that describes what I try to capture in a lot of my work. It is the plant and animal life of a particular region or period – from the Greek biote meaning way of life, or bios, meaning life.

Life changed quite a bit for me when, in late 2016, I took a job. I hadn’t had a full-time position in 22 years, and found myself busier than ever, with plenty of ideas for art and shows scheduled. I was determined to be a full-time artist and work too. I started drawing during my breaks at the office.

I had been missing paper and pencil, and was contemplating making work with less color. I ended up tracing old botanical drawings I had done in a sketchbook, and playing with variations of them. These were immensely satisfying because they weren’t identical, but had the visual alliteration I was looking for. The replication was soothing, and they went quickly. Some were traced lightly, some heavily with charcoal. When done, they could be further edited, put into paintings backward or upside-down, buried under wax or burnished over the top of color and other details. Thousands of possibilities were before me. I layered and encased them inside the wax, like a bug in amber.

Speaking of bugs, the Velocity Series was inspired by a small insect – a planthopper found only on English ivy. I had read an article about some scientists in the U.K. who had discovered this tiny insect that had evolved a mechanical gear, enabling it to jump extraordinarily fast. To put it in perspective, a person would be utterly destroyed if catapulted at the same velocity.

My imagination started a slow jog and then it flew. I worked for months with this bug happily perched on a branch in my mind. Many of the paintings began referencing insects. Wings, hives and swarms began to appear, as did both industrial and botanical elements. The Velocity Series were simply an abstract depiction of the ‘jet wash’ I imagine these bugs left in their wake.

The mechanical gear at the top of the insects’ hind legs was apparently the first time a functioning gear had ever been found in an insect. It fascinated me. Especially interesting was, as the bug molted, the gear phased out. Once mature, the bug jumped like every other bug jumps–more friction-based than mechanical. Without the ability to repair itself, the risk of keeping such a feature was simply too great. The gear was basically a mechanism to get it through what I like to think of as adolescence. What a great bit of engineering. What great design!

Speaking of design, it seems it has always borrowed from nature. Usually humans are the ones imitating the marvels of natural beauty and functioning, but this time it seemed the other way around! Then again, perhaps the ‘mechanical gear’ had been in nature all along, but being so young and self-absorbed, we humans consider it our own invention. In any case, this insect’s special design made its way into my paintings, not in the form of an actual gear per se, but in the form of abstract whirling ‘flower’ gears, wing forms, hives, clusters, rivets, ducts, and imagery with ever so faint a mechanical feel. The industrial elements were far from realistic, but referential, and they began blending with my ongoing themes of botany and biology.

The bug I was so enamored with, called the Issus Coleoptratus, was a tiny, perfect mechanical/insect hybrid to me. I am quite in love with the idea of hybrids. An earlier idea for this show was to paint abstract versions of hybrids. I wanted to blend animal with insect, flower with bug with goat with bloom, dragonfly with tree . . . whatever came about. Instead, I ended up blending nature with industrial elements, but will certainly continue hybridizing things both animal and mechanical. This blending represents my lifelong belief that we are all the same. For me it’s absurd to think an animal is much different from a person, or an insect that much different from an orchid.

I understand the big brain stuff, and the biological differences between plant and animal cells, but cells are cells, and if a bug can evolve a gear, why couldn’t a flower grow an arm, or a person a petal. It’s the equity of it that I adore. I’m in love with the idea we are all one thing. I disdain the differences. My abhorrence for racial inequity has been lifelong. As a child it made no sense to me, and as an adult I’m still baffled. Why, if we are essentially the same stuff as all other stuff, would we make a distinction?

To me, hives are homes, eggs are seeds, seeds resemble rivets, metal is metabolic, pipes are veins, concrete is flesh (particularly fascinating is the design of self-repairing concrete), wings are translucency which is water and water is life. People are people. In my art, the soft and the rigid blend to make beauty that is neither male nor female. Humans will soon blend their tissues with gadgets, have chips embedded inside them, utilize those google-glasses (whatever those were), and hopefully grow wings.

Perhaps my next show will feature what I call function-clusters–I think of them as a morula only with a mechanical twist, and hope to execute new work that reflects the complicated nature of nature, cells, hybrids, technology, industrial elements, and of course, my beloved botanical elements.

BIOTA

Biota is a succinct word that describes what I try to capture in a lot of my work. It is the plant and animal life of a particular region or period – from the Greek biote meaning way of life, or bios, meaning life.

Life changed quite a bit for me when, in late 2016, I took a job. I hadn’t had a full-time position in 22 years, and found myself busier than ever, with plenty of ideas for art and shows scheduled. I was determined to be a full-time artist and work too. I started drawing during my breaks at the office.

I had been missing paper and pencil, and was contemplating making work with less color. I ended up tracing old botanical drawings I had done in a sketchbook, and playing with variations of them. These were immensely satisfying because they weren’t identical, but had the visual alliteration I was looking for. The replication was soothing, and they went quickly. Some were traced lightly, some heavily with charcoal. When done, they could be further edited, put into paintings backward or upside-down, buried under wax or burnished over the top of color and other details. Thousands of possibilities were before me. I layered and encased them inside the wax, like a bug in amber.

Speaking of bugs, the Velocity Series was inspired by a small insect – a planthopper found only on English ivy. I had read an article about some scientists in the U.K. who had discovered this tiny insect that had evolved a mechanical gear, enabling it to jump extraordinarily fast. To put it in perspective, a person would be utterly destroyed if catapulted at the same velocity.

My imagination started a slow jog and then it flew. I worked for months with this bug happily perched on a branch in my mind. Many of the paintings began referencing insects. Wings, hives and swarms began to appear, as did both industrial and botanical elements. The Velocity Series were simply an abstract depiction of the ‘jet wash’ I imagine these bugs left in their wake.

The mechanical gear at the top of the insects’ hind legs was apparently the first time a functioning gear had ever been found in an insect. It fascinated me. Especially interesting was, as the bug molted, the gear phased out. Once mature, the bug jumped like every other bug jumps–more friction-based than mechanical. Without the ability to repair itself, the risk of keeping such a feature was simply too great. The gear was basically a mechanism to get it through what I like to think of as adolescence. What a great bit of engineering. What great design!

Speaking of design, it seems it has always borrowed from nature. Usually humans are the ones imitating the marvels of natural beauty and functioning, but this time it seemed the other way around! Then again, perhaps the ‘mechanical gear’ had been in nature all along, but being so young and self-absorbed, we humans consider it our own invention. In any case, this insect’s special design made its way into my paintings, not in the form of an actual gear per se, but in the form of abstract whirling ‘flower’ gears, wing forms, hives, clusters, rivets, ducts, and imagery with ever so faint a mechanical feel. The industrial elements were far from realistic, but referential, and they began blending with my ongoing themes of botany and biology.

The bug I was so enamored with, called the Issus Coleoptratus, was a tiny, perfect mechanical/insect hybrid to me. I am quite in love with the idea of hybrids. An earlier idea for this show was to paint abstract versions of hybrids. I wanted to blend animal with insect, flower with bug with goat with bloom, dragonfly with tree . . . whatever came about. Instead, I ended up blending nature with industrial elements, but will certainly continue hybridizing things both animal and mechanical. This blending represents my lifelong belief that we are all the same. For me it’s absurd to think an animal is much different from a person, or an insect that much different from an orchid.

I understand the big brain stuff, and the biological differences between plant and animal cells, but cells are cells, and if a bug can evolve a gear, why couldn’t a flower grow an arm, or a person a petal. It’s the equity of it that I adore. I’m in love with the idea we are all one thing. I disdain the differences. My abhorrence for racial inequity has been lifelong. As a child it made no sense to me, and as an adult I’m still baffled. Why, if we are essentially the same stuff as all other stuff, would we make a distinction?

To me, hives are homes, eggs are seeds, seeds resemble rivets, metal is metabolic, pipes are veins, concrete is flesh (particularly fascinating is the design of self-repairing concrete), wings are translucency which is water and water is life. People are people. In my art, the soft and the rigid blend to make beauty that is neither male nor female. Humans will soon blend their tissues with gadgets, have chips embedded inside them, utilize those google-glasses (whatever those were), and hopefully grow wings.

Perhaps my next show will feature what I call function-clusters–I think of them as a morula only with a mechanical twist, and hope to execute new work that reflects the complicated nature of nature, cells, hybrids, technology, industrial elements, and of course, my beloved botanical elements.

Bolus

Sold

Sold

works on paper

ELEGANT MONSTER 2, Acrylic, India Ink on Translucent Yupo Paper, 25 x 38 in.

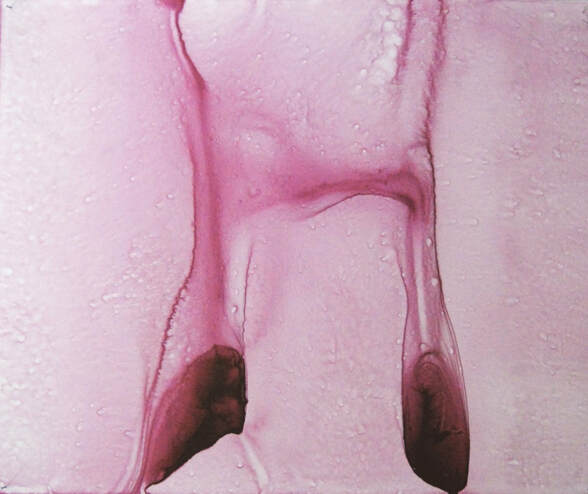

MEDULLA 3

Acrylic on Yupo Paper, 15 x 18 in.

Acrylic on Yupo Paper, 15 x 18 in.

MEDULLA 1

Acrylic on Yupo Paper, 15 x 18.5 in.

Acrylic on Yupo Paper, 15 x 18.5 in.

ENTELECHIA 9, Charcoal Pencil, Acrylic, Walnut Ink, India Ink onYupo Paper, 6.5 x 4.25 in.